The FCC to Public Safety…

03.29.2010 by Andrew M. Seybold

Unfortunately, it appears that the recommendations are based on faulty assumptions topped with major political pressure from a variety of sources including the executive branch of the government.

You Don’t Get D Block But You Do Get Funding

On Tuesday, March 9, 2010, the FCC met with a number of public safety executives and members of the vendor community in Las Vegas. Not an open meeting, this was by invitation only and the group was kept small. Since all of these types of meetings must be on the record, the FCC published the slide presentation it gave as well as an Ex Parte that discusses the meeting in some detail. While I was not invited to the session, I have talked with a number of people who were there, read a number of reports, and reviewed the FCC’s slides.

It did not take the FCC long to get to the bottom line of its recommendations to be included in the March 17 broadband report to congress, nor did it take long for both the public safety and vendor communities to push back. Unfortunately, it appears that the recommendations are based on faulty assumptions topped with major political pressure from a variety of sources including the executive branch of the government.

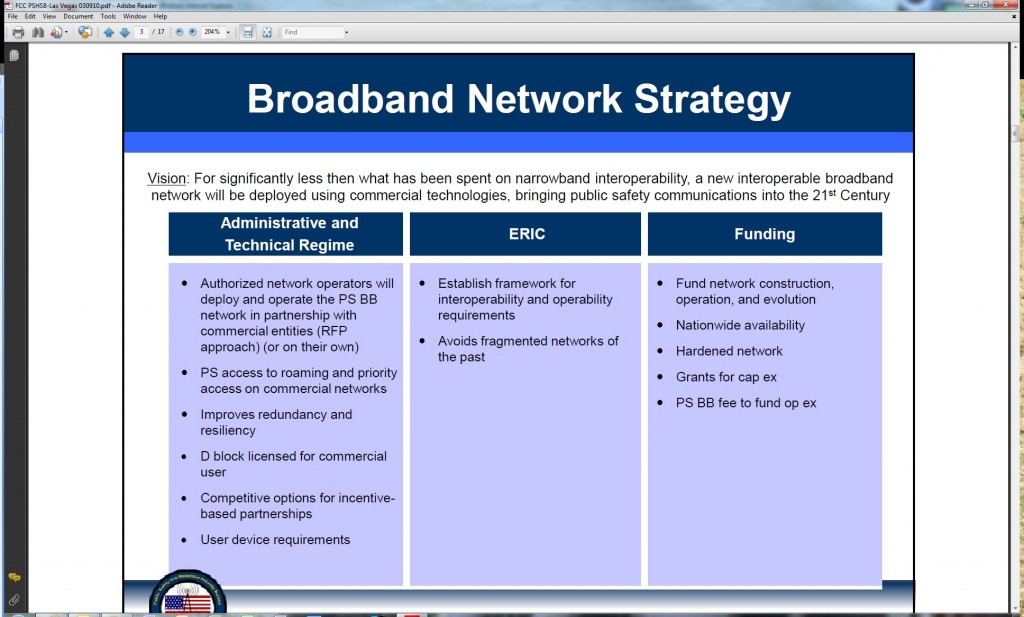

One of the first slides of the FCC presentation recapped its recommendations:

The entire slide deck can be viewed in PDF format attached to this COMMENTARY. In this recap slide, we see that the FCC is recommending that the D Block be auctioned AND that it be auctioned without any of the previous public/private partnership requirements that were attached to the failed D Block auction. Instead, the FCC offered up the idea that in addition to the PSST 10-MHz block of spectrum, public safety would be able to roam across all of the commercial operators’ networks so load sharing could be employed. Apparently the FCC was unimpressed by the NYPD white paper and the filings of several major carriers that proved, to me at least, that 10 MHz of spectrum is not enough. The FCC’s reported response to this data was that it did not feel what had been submitted made a compelling case for more spectrum today, but if more spectrum is needed later, perhaps some 600-MHz spectrum could be allocated. (Spectrum spread out all over the bands is the primary reason first responders HAVE an interoperability problem to begin with!)

I find it interesting that while the FCC seems to be measuring public safety data usage by today’s use patterns (mostly on commercial networks with limited access), it is at the same time acknowledging commercial operators’ “great need” for broadband spectrum into the future and is committed to allocating another 500 MHz to broadband over the next ten years. The data I have reviewed from NYPD, AT&T, and Verizon show heavy and growing data usage today and, like the commercial side, the number of new applications is increasing. Further, if the D Block is to be auctioned with no requirement to share with public safety, my discussions with network equipment providers indicate that a guard band will be needed between the D and PSST blocks of spectrum. Since the FCC has not included any spectrum for a guard band, it will have to come either from the D Block, the PSST block, or both. This would mean that the PSST block would be capable of only 3.75 MHz of LTE and not the 5 MHz that should be available.

Further, many commercial operators I have talked with admit that the value of the D Block is questionable for the same reason: 5 MHz (5X5) is not enough spectrum for LTE in metro areas. The network operator would have to have existing 3G capabilities to be able to switch customers between 3G and LTE. If a new network operator were to purchase this spectrum, it would not serve its needs for very long. The fact is that 5X5 is not enough spectrum for either the public safety community or a commercial operator. However, 10X10 would work for the public safety community and it could use all of the spectrum without having to provide a guard band. It could also be used in rural areas on a shared basis to provide broadband to rural America, for the Power Grid, for education and healthcare, and for governmental agencies.

The FCC asked for data on data usage. Now that it has received lots of data, it is negating it because it is based on usage of one dedicated network (New York City’s) and on existing commercial 3G networks on a shared basis. And projections for future data growth, mission-critical voice, and other services are being discounted. This shortsighted view is exactly why the public safety community continues to receive less than what it needs to effectively do its job. If I were a skeptic, I would think the commissioners’ attitude is that most of them won’t be around when the FCC has to face the issue of public safely not having enough spectrum, yet again, or that this thinking is coming directly from the executive branch’s experts in the form of the four or five Googlets working with them. (Google CEO Eric Schmidt has said publically that we are not approaching a spectrum shortage because “there’s enormous spectrum becoming available through licensing programs, better radio design, faster computers, and so forth.” This is a common view from those who do not understand radio and the spectrum, and don’t take into account the backhaul from zillions of radio sites.)

Back to the Meeting

The FCC also put forth some figures. The first was that the public safety grade system to cover 95% of the population would require 41,000 cell sites. This is probably a good number, but it claims that because many of these sites are already established either as commercial or existing public safety sites, the total capex for this construction would be just over $6 billion. I don’t have a clue where it came up with that number but I dispute it. First, even if that covers the cost of site improvements and radio systems, it does not include the backhaul (fiber or microwave) that would be needed at non-commercial sites or many of the other requirements of what are considered to be public safety hardened sites. The FCC also claims that this work can be completed by 2015, which is a departure from its usual “it will take 10 years” and this would probably be a realistic timeframe if the public/private partnerships were in place today and work had begun today. However, it appears that none of this will be formally resolved this year so it will drag into 2011 (ten years after 9/11). By then, the two major network operators will have already completed a great number of their urban sites so co-locating on them will cost more money for retrofits (commercial operators cannot be expected to harden their sites based on some future FCC requirement).

The FCC is making a serious mistake in recommending in its broadband report that the D Block be auctioned, and further, auctioned with no requirements for public safety sharing of any kind. I think there are capacity issues for both the public safety community and the D Block winner and there are guard band issues that will take spectrum from one or both. If this happens, it will take only a few years to prove that the FCC usage models were wrong, but by then the public safety community will have received the short end of the stick yet again. For any in the government who point to the D Block auction as paying down the national debt, think about this: If the D Block sells for $3.75 billion, and I think that’s high, it will pay off exactly ONE DAY of our national debt!

Sharing Networks

The FCC states that it will make sure all of the commercial operators are required to share their spectrum on a nationwide roaming basis with the public safety community. There is flawed logic in this as well. First, there is the issue with building devices that can cover the entire 700-MHz spectrum. It appears from work we have done in this area that in order to cover the A, B, C, D, and PSST blocks of spectrum, each device will require multiple diplexers, filters, and other components that will drive up device costs. But it does make sense to have this capability built into radios. It also makes sense to have 3G capabilities built in for the next five or so years so that during network construction, public safety customers could roam on both 3G and 4G as needed since it will take a number of years to build these networks, even with the help of the commercial operators.

The biggest problem I have with commercial network sharing is that if the PSST block is not enough spectrum, sharing will occur on a daily or weekly basis for what can be considered normal incidents. Fires, bank robberies, airplanes down, and all sorts of local emergencies will tax the PSST band to the point where some of the units will have to be moved over to commercial services. However, at the same time PSST systems require the use of peak resources, commercial operators will be busy with peak demand levels from the public and the news media. The issue here is what level of priority public safety customers will really have. In one type of priority, they have to wait until there is capacity in their cell sector, meaning someone else has to drop off. But when there is an incident, commercial customers grab onto a wireless connection and don’t let go for fear of not getting it back. The ONLY way to provide true priority for public safety is to require what is known as “pre-emptive” priority, which means that when public safety needs spectrum, commercial users’ sessions can be terminated to make room for public safety. None of the network operators like this idea because their customers would take issue with this policy.

In short, there are both technical and operational problems with the FCC’s vision of network sharing and the public safety community. While it is logical to shift some of the load away from the public safety network (administrative and other non-mission-critical communications) it is not logical to assume that public safety will have sufficient access to commercial networks during times of major incidents—even local incidents. This is one more reason that this FCC recommendation to congress regarding the PSST and D Block is not the correct recommendation.

My analysis of the FCC’s comments at this meeting is that it is recommending that public safety providers receive federal funding to build out their nationwide system ONLY if the public safety community agrees that the D Block should be put out to auction. The FCC will not support public safety in it efforts to convince congress to hand over the D Block and it will not support funding unless the D Block is auctioned.

If I had been given the task of writing the recommendation for congress for the public safety portion of the broadband plan, it would have gone something like this:

When the D Block was first put up for auction, it was envisioned that there would be a true partnership between the public safety community and the winner of the D Block. However, no bid was received from a commercial operator due to many factors including the restrictions placed on the spectrum to ensure public safety access. If there had been a successful bid, both the commercial and public safety community would have had access to a full 20 MHz of spectrum (10X10 MHz) during normal conditions and public safety would have had access to more than its own 10 MHz of spectrum during major incidents through priority access to the D Block.

At that time, wireless data usage was still in its infancy and data requirements were modest for both public safety and commercial operators. Since then, the demand for data has more than doubled each year and on the commercial side it is now 5000% higher. Based on the data provided by the public safety community and the commercial network operators, *the commission* now believes 10 MHz of spectrum will not be sufficient for the public safety community.

Based on the information* the commission* has analyzed, the data usage models provided to us, and the fact that over time this spectrum will also be used for mission-critical voice as well as data services, *the FCC* now recommends the following:

- Congress no longer require that the D Block be auctioned.

- Congress direct the commission to license the D Block on a nationwide basis to the holder of the existing Public Safety 10-MHz license.

- Congress appropriate $12-$16 billion for construction of the new public safety broadband network.

- Congress provide tax incentives to commercial network operators that are already licensed in the 700-MHz band to enter into private/public partnerships with regional public safety entities.

If congress acts favorably on these recommendations, *the FCC* will quickly make the following changes to expedite the construction of this nationwide interoperable network:

- Permit the nationwide license holder to grant region-by-region approval for network construction by cities and counties.

- Promote by incentives the close cooperation between commercial networks and the public safety community to work together in network deployments.

*The commission* respectively requests that the above recommended actions for congress be given priority and the legislation needed to make these changes be completed during the current session of congress. Two of the major commercial network operators are in the process of building out their own 700-MHz broadband networks and it is imperative that the public safety community be able to work with these network operators to form private/public partnerships on a regional basis in a timely fashion.

*my words, not those of the FCC*

Of course my wording is not flowery enough for a document from the FCC to congress, but it does get the point across. One closing thought I cannot let go of is that the recommendations the FCC is making to congress in its broadband report are not based on data and information as the FCC chairman has said he would require going forward. Rather, politics have once again stood in the way of reason. I am not sure if this pressure on the commission came from the executive branch or others within the Internet community who are not conversant in the issues of bandwidth sharing and finite spectrum resources.

The public safety community has always had an interoperability problem, caused largely by being given too little spectrum in each band segment as it became available. The FCC and congress has an opportunity to change that this time around—but indications are that neither will act and once again the next FCC and congress will face the problems created by the current FCC. There is no doubt that these recommendations are both shortsighted and the wrong thing to do. Many within the FCC know and acknowledge this, but their hands are tied since some commissioners, including the chairman, have made their wishes known.

I wrote my first newsletter article about the interoperability issues facing the public safety community in 1981, and I have written about this problem almost every year since. What I would really like is to be able to write about how much progress we have made in building out the public safety broadband network, the new interoperability capabilities it brings to public safety, and some of the innovative ways it is being used to speed response times, solve crimes, and provide our first responder community with the same tools an 16-year old has today with an iPhone!

Andrew M. Seybold

[…] not based on reality. For example, the FCC appears bound and determined to auction the 700-MHz D Block instead of asking Congress to reassign it to the public safety community. The Commission seems to […]

[…] requirements. That it has taken a position with such a strong recommendation to have the D Block auctioned does not make sense to me. I think it would have been better if the PSHSB had modified the Broadband […]