More Bandwidth Please!

12.14.2015 by Andrew M. Seybold

So on the one hand the network operators are saying they need more and more spectrum and on the other it appears they are not being good stewards of the spectrum they have. There is a disconnect between these two for sure.

The wireless carriers are screaming they need more spectrum that can be used for broadband services, Congress believes wireless and broadband are now synonymous, and the Executive Branch of the federal government led by the President and being executed by the NTIA is ordering more of the nation’s federal spectrum released or at least made available for sharing. Meanwhile, the FCC is readying the 600-MHz incentive auctions to replace UHF-TV channels above channel 32 with more spectrum for commercial broadband (with the exception of Channel 37 which is reserved for Radio Telescopes in the U.S.)

Yet the other side of the story makes me wonder how all of this “new” spectrum will be used. Within only the last six months we have seen all of the major carriers increase the amount of data per user in their monthly allocations (either with or without a contract), and more users are streaming more videos to their devices. Most recently, AT&T bought DirecTV and is streaming DirecTV programming over its wireless broadband system while Verizon has established its own video broadcasting service with Go90 Mobile, which it is also pitching to the gaming community.

So on the one hand the network operators are saying they need more and more spectrum and on the other it appears they are not being good stewards of the spectrum they have. There is a disconnect between these two for sure. Wireless network operators say consumers are demanding more bandwidth for streaming video services, but is it really the highest and best use of a limited resource to provide everyone on a broadband network with access to tons of video, some of which is high-definition and therefore uses a lot of bandwidth. I often wonder how different it would be if our spectrum was administered the same way it is in Japan. There it is leased to the network operator on a yearly basis so instead of a one-time windfall, the government receives income every year. The license requires wireless coverage over a large percentage of Japan (yes, I know Japan is smaller than the U.S.) AND most importantly for this discussion, the network operator must pay a onetime fee for each device it puts on the network. The result is that the wireless operators appear to be better able to manage their bandwidth allocations while consumers do not seem to be missing out on any content.

While writing this I glanced at my email on the other screen and saw an announcement just in from Verizon saying that from today until January 6, 2016, any existing or new customer who adds a device to an XL or XXL plan receives 2 GB of free data every month for life! The example given is a family of four with an XL plan that gives them a shared pool of 12 GB of data. Upgrading all of the devices adds 8 MB of data to the plan for life so they now have 20 GB per month for the four of them to share. It is difficult to fathom the usage models for spectrum. T-Mobile, the network operator with the least amount of spectrum of the top four, seems to be giving each user more and more data almost every month. I believe this puts it in a “must win” situation for the incentive auction, which might not prove out depending on how many other bidders participate.

Spectrum is a finite resource. Yes, we are learning how to employ spectrum higher in the bands and yes, with advances leading up to LTE or 4G the engineers and standards bodies are able to make more efficient use of the spectrum. However, it is still a finite resource. We cannot make any more of it and consumers are NOT the only people in the world who need access to it. Today, Public Safety, railroads, highway and transportation companies, utilities, airlines, the U.S. military (all branches), all of the three-letter organizations within the federal government, and many, many more entities need access to spectrum. Some of these users can make do with narrow slices of spectrum but some are growing their own demand and will need broadband services—not simply broadband services over commercial networks that are “best effort” networks, but over networks that are as near to mission-critical as they can be designed and built.

You might have read that the Public Safety community will have its own nationwide broadband network that will be built, operated, and maintained by a public/private partnership led by FirstNet, which is an independent authority set up under the NTIA to develop the network and put it into operation. This network is needed because during times of disasters, or even 4th of July celebrations, the commercial networks can become so congested that our first responders cannot rely on them. However, the Public Safety community will not be able to give up its Land Mobile Radio channels and move all of its operations to the new LTE network because their voice systems are much more robust. However, there is a serious problem in eleven major metro areas because when Congress authorized FirstNet, it demanded a provision in the law to take back the Public Safety community’s right to use unfilled UHF-TV channels. Boston, for example, uses all of the typical Public Safety spectrum allocations PLUS two of the shared TV channels. (Channels 14 and 16). The upcoming loss of this spectrum will have a detrimental effect on Public Safety’s ability to “Protect and Serve” in these eleven areas. Add to that the fact that there will be hefty relocation costs, if the services can in fact be relocated, but Congress made no provisions for funding the moves.

We cannot simply keep taking spectrum away from one user for another and then not using it in the highest and most efficient manner. We cannot expect that all of the other users can simply make do with commercial wireless broadband services. It is unfortunate that those making the decisions in DC grew up with cell phones and never had the experience of using push-to-talk, walkie-talkie, or other communications devices. To them, interoperability is being able to dial any other phone in the world and talk to the person who answers. They do not understand others’ needs to use the spectrum in a multiplicity of other ways.

The statistics for commercial broadband usage continue to predict, and prove, that demand is outstripping the supply of spectrum or network resources. However, what the statistics don’t show is that much of that higher demand for broadband services is a self-inflicted wound on the part of the network operators with their offerings of new, bandwidth-consuming content which, perhaps, is not the highest and best use of the spectrum.

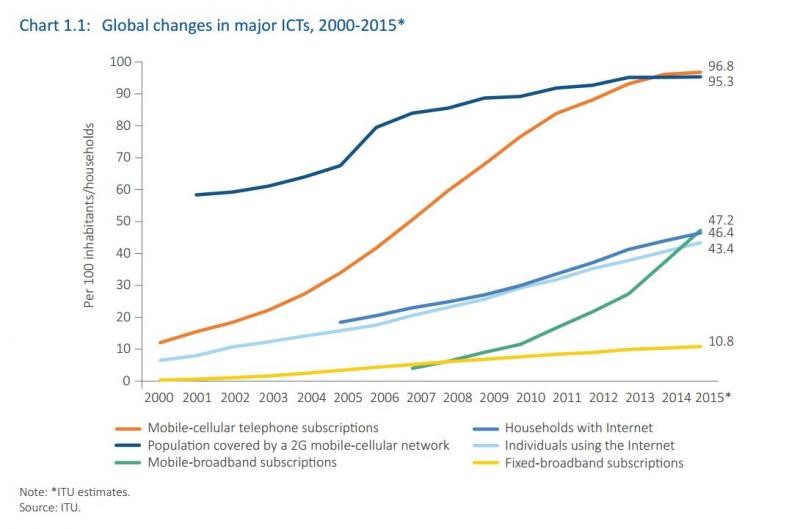

The chart below, reprinted from the most recent ITU Report, shows the actual growth of all of the broadband services in play today. There are many, many other studies showing the rapid explosion of wireless broadband, and we all know that more devices with more capabilities and higher resolution are coming our way. The higher the resolution, the more bandwidth is consumed delivering that data or video to the consumer or business user and the less bandwidth there is for others in the same cell sector. After all, this is not about how much spectrum a network operator has across the United States or even within a city. It boils down to how much spectrum a wireless operator has been able to deploy on a cell sector basis. Within each cell sector the total amount of data is fixed. The amount provided to any given user is based on two things: how many other people are in that same cell sector consuming broadband and how much the network operator limits the capacity in that cell sector.

The entire prospect of 5G, supposedly, is to build out thousands and thousands of small cells so the same amount of spectrum can provide much more capacity and help meet demand. In theory, this is a great idea. In reality, it is already in play since network operators are off-loading to Wi-Fi wherever possible to move people off the network. However, each small cell requires a path back to the network and small cells are not standalone devices. In order to be included in the network, they must be connected to the network. Today’s Wi-Fi hand-offs are possible because the path back to the network is from the Wi-Fi access point, usually over a wired, cable, or fiber link, to the Internet where it is routed to the network operator’s back-end and blended in with the licensed wireless network so it appears to be seamless. This is what 5G will look like when it is implemented.

There is no solution to this circular path we are on. More demand for more different types of broadband services, network operators delivering more streaming content, and the federal government believing the highest and best use of any spectrum today is broadband (especially since it can be auctioned for big bucks). At some point someone at the FCC, within the Executive Branch of the government, or within Congress will have to get real about spectrum allocations. They need to understand there is a value to having other than broadband systems and not all wireless communications should be relegated to the world of commercial operators and their broadband networks. We have to find a way to make better use of the spectrum we have. Using 5G and more of it is moving in that direction, but at the same time it is incumbent on those who are licensed on the spectrum and selling wireless services to others to take better care of the resource they are using or at some point it will collapse under its own weight.

Andrew M. Seybold