FirstNet Brings Changes to Unified Incident Command

09.25.2013 by Andrew M. Seybold

FirstNet will be the best thing that has happened to Public Safety in years, but it will require some changes in how law enforcement, fire, EMS, and other agencies work together and coordinate at incidents. Don’t wait for FirstNet to come to your area, get a jump on it now and be ready when it is.

As we learn more about FirstNet and its progress toward a nationwide broadband network, there are a number of matters state and local Public Safety agencies can and should address prior to the network being deployed. The FirstNet Board of Directors has repeatedly stated that while the network will be nationwide in its reach and capabilities, the content that flows over the network will be under local control. This is an important point since local agencies tend to operate in different ways both during routine use and during incidents.

When working with the FirstNet system, one of the most significant differences is that all of the agencies within your jurisdiction will be sharing the same network capacity. Today, most Public Safety agencies within a single jurisdiction use their own set of radio channels (or share a trunked network)—police are on their own channels, fire and perhaps EMS are on another, and EMS has additional channels for talking directly to hospitals. If police and fire need to talk to each other, two or more radio channels are tied together at a radio console located in the dispatch center for the duration of the needed communication. Fire, police, and EMS generally operate at the same incident without interfering with each other’s transmissions. Of course, this is one reason there are voice interoperability issues today.

With the FirstNet system, all of the departments responding to the incident will be sharing the same radio system (FirstNet) for data and video. This will not present a problem during normal patrol and other types of day-to-day operations since each unit in the field uses only a small portion of spectrum and communicates only with a dispatch center or perhaps a few other units during a local incident. However, when several agencies are involved in an incident of any size, and all need access to data and video, it is possible that in some cases there will not be enough network capacity to go around.

I will try to illustrate this with an example. I am not using real capacity and data speed numbers here, I am using numbers that will give you an idea of the issue. First, it is important to note that the FirstNet data and video system is cellular-based, built on the principle of multiple cell sites in a given area. Further, each cell site is usually divided into three equal 120-degree sectors. The capacity within any cell sector will normally be the same. In this example, let’s say that the capacity from the network down to the field devices is 20 Megabits per second (Mbps) and the capacity from field devices up to the network is 10 Mbps. (Following the Internet model, LTE provides a higher data rate down to the device than up from the device. In the Public Safety world, this model may not always be correct.)

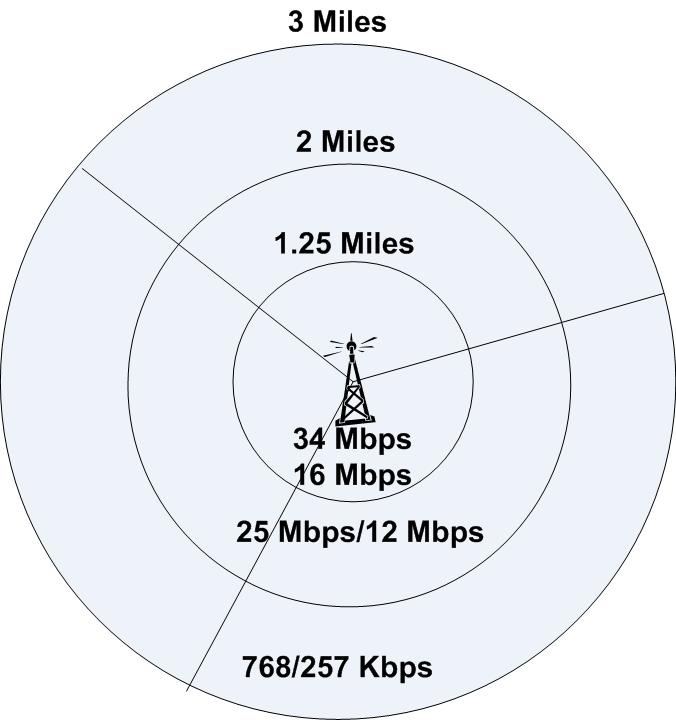

Each cell sector will have this same capacity and this capacity is what is available close to the center of the cell. As you move further away from the center, capacity and data speeds will be reduced until at the very edge of the sector coverage you will experience sub-1 Mbps performance. However, for this example we will be staying with our model of 20 Mbps down and 10 Mbps up. Let’s look at localized incidents.

Each cell site is usually divided into three 120-degree sectors. Each sector has the same capacity. The closer you are to the center of the cell, the better the data speed in both directions.

Suppose there is a fire in a building. Chances are that this building will be in coverage of a single cell sector so the maximum available bandwidth will be 20 Mbps down and 10 Mbps up. Response to this type of fire will include the fire department with multiple engines, ladder trucks, rescue, and other vehicles. EMS will respond with one or more units in case there are any medical emergencies during the incident, either with people inside the building who might have been injured or overcome by smoke, or if first responders at the scene receive any kind of injury. And of course, police will respond to help with crowd control, closing roads, and ensuring that order is maintained in and around the fire.

All three agencies will need access to the FirstNet system. In route, fire vehicles might be receiving directions, traffic information, floor plans, and hazardous material locations within the building, locations of fire hydrants, and other relevant information. The first-in officer will be receiving a list of incoming equipment so it can be placed where it is most needed, and perhaps some vehicles will be receiving a video feed from a fixed camera in the area that has a view of the building. All of this data will assist those responding in placing the incoming equipment to their advantage and give them an idea of what they are up against.

As police respond they will be receiving updates from the scene, perhaps video from the first fire engine on the scene, traffic information, and more. EMS units will receive the same traffic and route information and any other available information regarding the incident. None of this will be a problem while responding because each unit will most likely be in a different cell site or cell sector until the point where they converge at the incident. At this point, all of the data and video in both directions will be using only one or perhaps two cell sectors.

All three agencies will be sharing the 20 Mbps down and 10 Mbps up from the incident. This is where things will be different from what they are today. Who will manage the need for bandwidth during an incident? The prime Incident Commander (IC) does not have time, and in this case the IC will be attached to the fire service. This is where the Incident Command system needs to be updated to include more functions in a Unified Incident Command where all three services are represented and how much capacity is needed by each will be determined in real time. In practice, this should not be controlled by any of the ICs but rather communications personnel at the scene or back at the dispatch center.

In some of my earlier speeches I jokingly said that first responders need to hire the people who sit in the ESPN truck next to a stadium because they are very good at managing bandwidth and switching cameras as needed. But it is no joke that these types of attributes will be needed during incidents. Suppose, in this example, the fire department was using several cameras to send video information about the fire and exposures to the IC and others for their information and taking up a lot of the bandwidth, and in the middle of the incident one of the EMS crews was working on a patient and was not sure if he/she was bleeding internally. Since ultrasound handheld units can be used to see inside a patient, they are instructed to perform an ultrasound examination and stream it to the hospital, but when they try to access the network they find that there is not enough bandwidth to transmit the ultrasound. How does the EMS crew gain access to sufficient bandwidth to be able to send the ultrasound? The only way is for someone else to stop transmitting, reduce video quality, or slow some data streams so the ultrasound can be sent.

Meanwhile, the police may also need to send some video from the scene or pictures to help identify a suspect who is watching the fire. They might need to gain access to the bandwidth they need. And then there are police and others who may be on routine patrol in the area, needing access to data to run license plates or other information. As you can see, the FirstNet system will need to be shared by all agencies involved in both normal activities and incidents. Again, during normal patrols and activities, with first responders being spread out over a city or county, there will be sufficient capacity for these tasks. The capacity limits only become an issue during incidents either within a confined area where only one or perhaps two cell sectors offer network coverage or during major incidents when there are many first responders in many different areas needing lots of video or other large-data services.

The FirstNet system will provide various levels of priority and quality of service (both are features designed into LTE). However, static priority assignments will not work in this instance. Instead, priorities will need to be changed on the fly; again by someone overseeing the scene or perhaps by software developed for the task, but even this will require a person at some point in the chain to assist in network capacity management.

It is during such incidents that all of the local agencies will have to coordinate among themselves more than ever before. This will become second nature to first responders over time, but my advice is to start now to set up the necessary command structures to ensure that when the FirstNet system is up and operating there are no glitches in the beginning. I have nightmares about the first time there is an incident after the network is operational in an area. Lots of first responders head to the scene, arrive, and then without thinking turn on their dash cams and other video sources to help other responders coming to the scene to see what is happening and to better inform the dispatch center. The result could end up being that the network will collapse and none of the videos will pass through the system.

If this happens, first responders will blame the network for the failure and probably not trust it again for a very long time. In essence, this would be a repeat of when iPhones were first introduced and too many of them were used in a single cell sector. Citizens (and first responders) don’t understand that while network capacity is based on many factors, when too many people are within a single cell sector it can become overloaded, at first slowing data rates and then perhaps failing altogether. However, if there are realistic expectations and pre-planned scenarios in place, the system will work, remain working, and prove to the first responder community that it is a viable system that can and will assist them in their jobs, help with their initial responses, and help them manage many different types of incidents.

When FirstNet is first turned on in your area of operation, it will go through a period of testing and then be deemed available for service. Once this happens, the first incidents in which data and video are used will determine how the first responder community views the network and its value. If the capacity is managed well from day one, it will be a success. However, if departments do not have their acts together and have not learned how to work together, the first experience of some first responders may not be a positive one.

Interagency planning is a must. A unified Incident Command, whether it is using ICS or NIMS, is a must. Having people and software management in place to manage the demand on this new network is a must! My suggestion is that each city and county begin working on plans to determine how to work with all of the various first responders. If you are using existing 3G or 4G commercial networks now, you understand that you have no control over the amount of bandwidth available to you. You share these networks with consumers and business users and network operators generally limit the speed of each user to ensure that the maximum number of users per cell sector can be served. But you can still use these networks in exercises, training, and during real incidents to practice allocating capacity to the various departments within your jurisdiction.

The successful roll-out of the FirstNet system in your area will depend on having an updated Incident Command structure. It will require a communications or network person on the scene or back at the dispatch center who will be able to assist you in allocating the available bandwidth, monitoring it, and perhaps even transferring some non-essential data and video to commercial networks during an incident in real time. It is possible, perhaps, that some of this can be accomplished by software that is monitoring your portion of the network, but for the best results it will take a knowledgeable person who ideally does not work for any one agency to be able to make network decisions on the fly.

FirstNet will be a boon to first responders. It will give them eyes and enable ICs and dispatch centers to see, in addition to hear, what is occurring at an incident. It will help enable more efficient decisions regarding the handling of the incident, but it will require additional personnel for incidents over a certain size. It will be the best thing that has happened to Public Safety in years, but it will require some changes in how law enforcement, fire, EMS, and other agencies work together and coordinate at incidents. Don’t wait for FirstNet to come to your area, get a jump on it now and be ready when it is.

Andrew M. Seybold